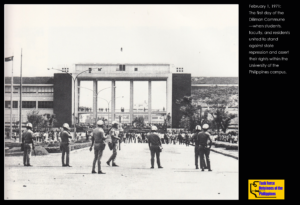

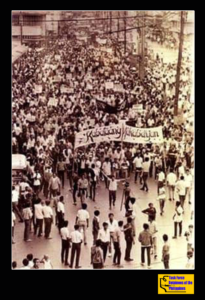

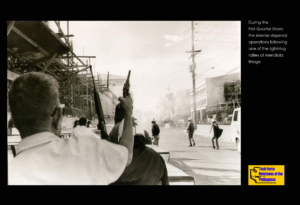

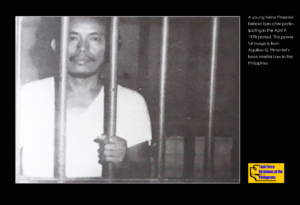

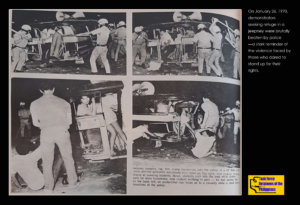

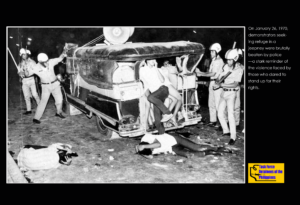

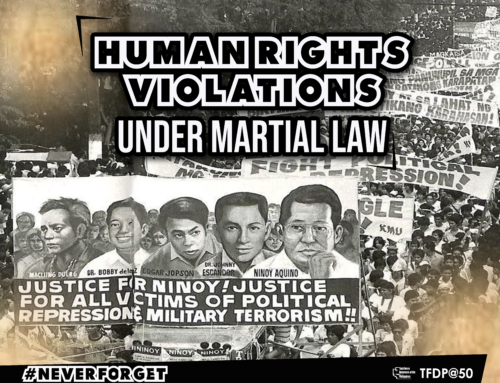

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Philippines was a nation on the brink of chaos. Economic disparity, rampant corruption, and widespread social unrest plagued the country. Student protests erupted across universities, labor strikes paralyzed industries, and the communist insurgency gained momentum in rural areas. President Ferdinand Marcos, facing the end of his second term and the threat of losing power, exploited these crises to justify an unprecedented move. Claiming that the nation was on the verge of anarchy, Marcos declared Martial Law on September 21, 1972. This allowed him to dissolve Congress, silence the media, arrest political opponents, and rule by decree, effectively establishing a dictatorship that would last for over a decade. The declaration was framed as a necessary step to restore order, but it plunged the Philippines into an era marked by human rights abuses, suppression of dissent, the concentration of power in the hands of the Marcos regime and unprecedented corruption that remains unmatched in Philippine history.